What climate change looks like?

When a glacier breaks up, the images can be breathtaking — and a sobering reminder comes along about our home.

Makliya Mamat / March 30, 2022

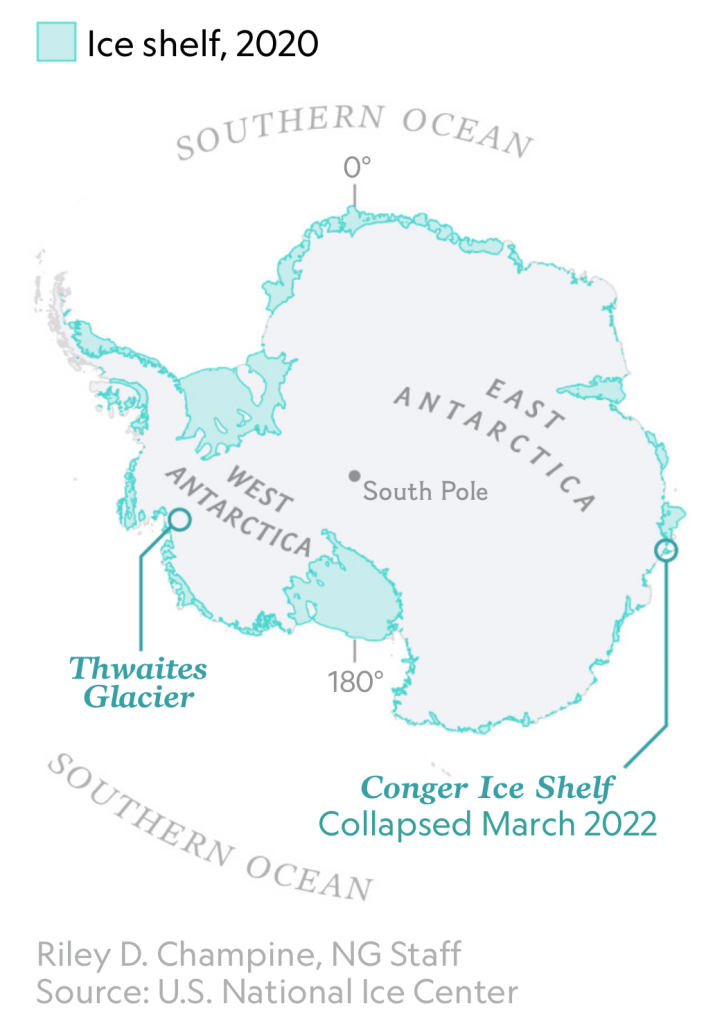

Not long ago, I read a news written by Alejandra Burunda on National Geographic, which reported the East Antarctica—the other, colder side of the continent—saw its first-ever ice-shelf collapse. The unexpected collapse highlighted the importance of—and uncertainty about—the continent’s ice shelves.

Their incipient demise, scientists fear, could be the beginning of more ice loss—and much more sea level rise that would affect countries all over the world.

When we think of what climate change looks like, we often picture of giant icebergs melting in the Arctic. It is true that the floating icebergs are typical images, though it is difficult to photograph climate change — a slow, subtle process that develops over time. But it’s so much more than that.

These images below, shot by photographers all around the world, show us how the planet is actually changing.

A neighborhood is flooded in Beaumont, Texas, a day after Hurricane Harvey came ashore in August 2017. The Category 4 storm caused historic flooding. It set a record for the most rainfall from a tropical cyclone in the continental United States, with 51 inches of rain recorded in areas of Texas. An estimated 27 trillion gallons of water fell over Texas and Louisiana during a six-day period. “Warmer sea water from our changing climate is causing tropical storms to be more wet and powerful,” photographer George Steinmetz said.George Steinmetz

Peia Kararaua, 16, swims in a flooded area of Kiribati’s Aberao village. Kiribati is one of the countries most affected by sea-level rise, photographer Vlad Sokhin said. During high tides many villages become inundated, making large parts of them uninhabitable. This photo was taken in an area that, when dry, is a soccer field. “Prior to this, a man moved his vehicle from the lower part of the field to the higher point, and the vehicle ended up being parked on an ‘island’ when the water came,” Sokhin said. “Young people started swimming there and playing when I took this shot. It was strange to see such a scene: happy kids swimming along the remains of the dead palm trees.”Vlad Sokhin/Panos Pictures

A woman walks through a cactus field in a drought-stricken area of western Somaliland, a breakaway state from Somalia. “In 2016 I came across a group of women washing their clothes in a roadside puddle — the only water they could find,” photographer Nichole Sobecki said. “We spoke for a while of the challenges they faced, of the animals they’d lost in the drought, and the wells that had dried up. Somalia has long been a place of extremes, but climate and environmental changes are compounding those problems and leading to the end of a way of life.”Nichole Sobecki/VII/Redux

Jorgen Umaq and his dogs traverse an icy area near Qaanaaq in northern Greenland. It is one of the northernmost towns in the world. Because ice thickness there has been declining, hunters like Umaq can’t travel as far as they could before, said photographer Anna Filipova. “Navigating this terrain was dangerous and difficult,” she said. “We needed to manually move the sledge and twice needed to rescue the dogs who had fallen into the cracks in the sea. … Each year, people lose their lives on the sea ice because of fast-changing conditions.”Anna Filipova

Bangladesh was recently ranked by research firm Maplecroft as the country most vulnerable to climate change, due to its exposure to threats such as flooding, rising sea levels, cyclones and landslides as well as its susceptible population and weak institutional capacity to address the problem. This aerial photo, taken by Ignacio Marin, shows where some homes used to be before the river washed them away. “From where I was standing, at the riverbank, it was hard to imagine that there were nine houses where I could only see water,” Marin said. “So I decided to fly the drone. Only then, watching the area from above, I realized the scale of the disaster.”Ignacio Marin/Institute

Sheep graze in the dry, dusty fields of Farmersville, California. “This image was made in 2014 while working on a short film about the ongoing drought in California,” photographer Ed Kashi said. “Tens of thousands of acres of arable land was turning to dust, massive orchards were being ripped out due to a lack of irrigation water, and farmers and ranchers who for generations had worked this land were wondering if their way of life was sustainable.” Intense droughts like the one that plagued California this decade are becoming more likely due to global warming.Ed Kashi/VII/Redux

Oil refineries are seen in Carson, California, in this 2017 photo taken by Edward Burtynsky for The Anthropocene Project, which explores how humans have contributed to climate change and the state the planet is in today. Part of the project includes a film, “Anthropocene: The Human Epoch,” that opens September 25 in 100 theaters across the United States.Edward Burtynsky/Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York/Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco

Two people are seen at an ice cave entrance on the Rhone Glacier in the Swiss Alps. Every summer, the glacier is covered with huge sheets of white fleece blankets to slow down its melting, according to photographer Orjan F. Ellingvag. “The fleece-covered cave attracts more and more tourists worried about global warming and wanting to see the remnants of a dying glacier,” Ellingvag said.Orjan F. Ellingvag

A wildfire burns in Tocantínia, Brazil, in September 2018. In the Cerrado region, wildfires are common for two reasons, said photographer Marcio Pimenta. One is extreme heat. The other is farmers clearing space for soybeans and livestock. Marcio Pimenta/Institute

A wildfire burns in Tocantínia, Brazil, in September 2018. In the Cerrado region, wildfires are common for two reasons, said photographer Marcio Pimenta. One is extreme heat. The other is farmers clearing space for soybeans and livestock. Marcio Pimenta/Institute

This aerial photo shows Ejit, an islet in the Marshall Islands, in 2015. The islands are threatened by rising seas. “I flew a drone above the island showing just how precarious its location is: Homes clinging to the edge of an eroding coastline as unrelenting waves chisel away at what remains,” said Josh Haner, a photographer with The New York Times. “After I saw what was happening on Ejit, I realized that climate change is not something nebulous that will only start affecting us in the future, but rather something happening right now. Residents are being forced to make the most difficult decision: Do they stay and build sea walls to buy some more time, or do they relocate?” Josh Haner/The New York Times/Redux

An iceberg floats near Tasiilaq in June 2018.

The average sea level has risen by about 7-8 inches since 1900*, according to a major climate report released by the Trump administration in 2017. Almost half of that has happened in the last 25 years.

What will the next 100 years look like? Or the next 20? How fast will the waters continue to rise, and when will it put human civilizations at risk? Much more questions needed to asked, and of course the answers to them needed to be researched, to be find. Therefore, we could make better decisions now for the future.

Some may ask Why? Because, this is our home.

Contents

Newsletter

- Updates from Makliya Notes will be delivered to your inbox.