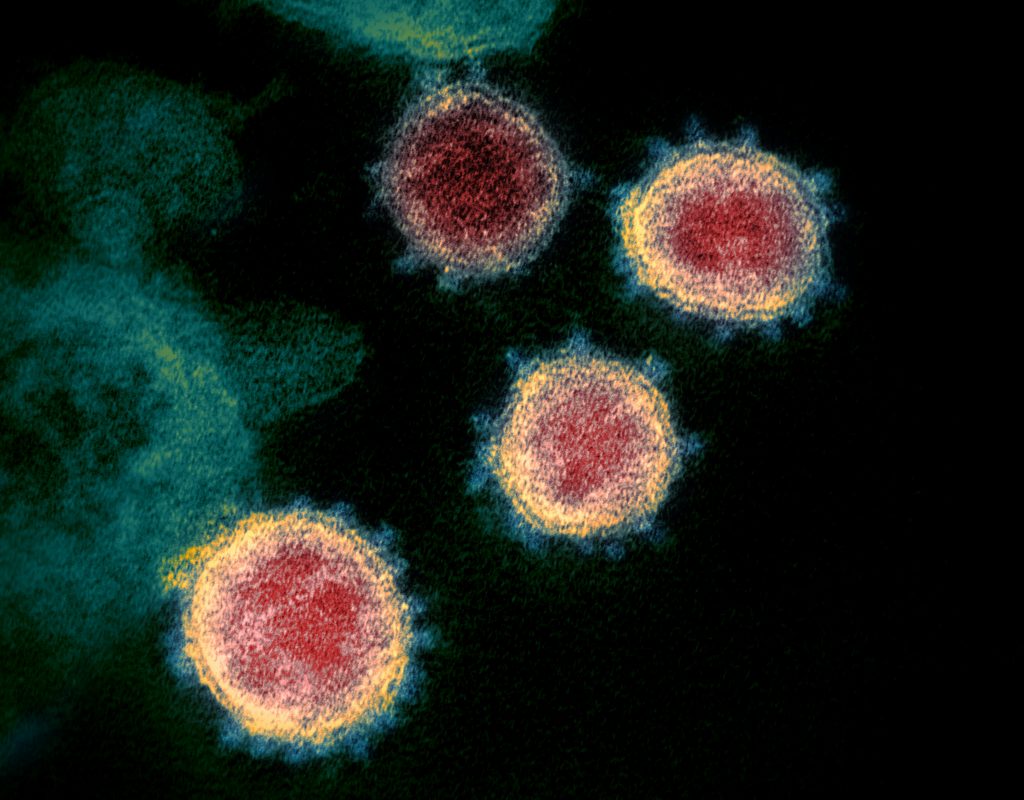

So we’ve gotten our coronavirus vaccine, waited the two weeks for our immune system to respond to the shot and are now fully vaccinated. Does this mean we can make our way through the world like back in the old days without fear of spreading the virus?

Many people think vaccines work as a shield, blocking a virus from infecting cells altogether. But in most cases, a person who gets vaccinated is protected from disease, not necessarily infection. The aim of vaccination is to induce a protective immune response to the targeted pathogen without the risk of acquiring the disease and its potential complications.

Every person’s immune system is a little different, so when a vaccine is 95% effective, that just means 95% of people who receive the vaccine won’t get sick.* These people could be completely protected from infection, or they could be getting infected but remain asymptomatic because their immune system eliminates the virus very quickly. The remaining 5% of vaccinated people can become infected and get sick, but are extremely unlikely to be hospitalized.

Vaccination doesn’t 100% prevent you from getting infected, but in all cases it gives your immune system a huge leg up on the coronavirus. Whatever your outcome – whether complete protection from infection or some level of disease – you will be better off after encountering the virus than if you hadn’t been vaccinated.

Vaccines Need Not Completely Stop Transmission

Efforts to arrest the spread of polio provide additional insight into the complexity of stopping an epidemic. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative and the World Health Organization recommend distinct vaccination strategies depending on the local context. In places where wild polio still exists, the oral polio vaccine (OPV) is key to slowing transmission. In areas where the wild virus has been eradicated, the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) keeps populations protected. Thanks to widespread immunization programs, the disease is on the verge of global eradication.

A study found that if a vaccine protects 80 percent of those immunized and 75 percent of the population is vaccinated, it could largely end an epidemic without other measures such as social distancing. That is, if the vaccine only prevents disease or reduces viral shedding rather than eliminating it, additional public health measures may still be necessary.

Research on seasonal coronaviruses suggests that SARS-CoV-2 could similarly evolve to evade our immune systems and vaccination efforts, though probably at a slower pace. And data remain mixed on the relationship between symptoms, viral load and infectiousness. But ample precedent points to vaccines driving successful containment of infectious diseases even when they do not provide perfectly sterilizing immunity.

If we look back, we will find that epidemic-prone diseases such as measles, diphtheria, pertussis, polio, hepatitis B—their progress shows that we actually don’t need 100 percent effectiveness at reducing transmission, or 100 percent coverage, or 100 percent effectiveness against disease to triumph over infectious diseases.