Thanks to revolutionary advances in medicine and public health, our patterns of disease have changed. Our current patterns of disease would be unrecognizable to our great-grandparents or, for that matter, to most mammals. We get different diseases and are likely to die in different ways from most of our ancestors (or from most humans currently living in the less privileged areas of this planet).

The diseases that plague us now are ones of slow accumulation of damage—heart disease, cancer, cerebrovascular disorders.

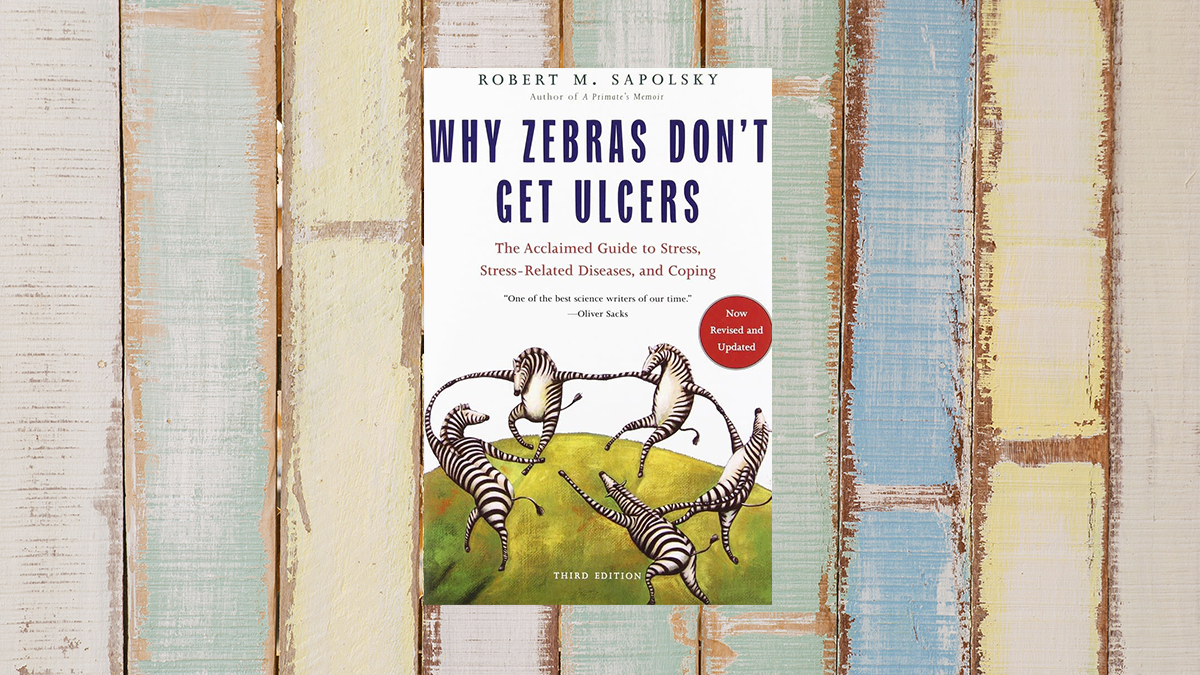

This book is a primer about stress, stress-related disease, and the mechanisms of coping with stress. How is it that our bodies can adapt to some stressful emergencies, while other ones make us sick? Why are some of us especially vulnerable to stress-related diseases, and what does that have to do with our personalities? How can purely psychological turmoil make us sick? What might stress have to do with our vulnerability to depression, the speed at which we age, or how well our memories work? What do our patterns of stress-related diseases have to do with where we stand on the rungs of society’s ladder? Finally, how can we increase the effectiveness with which we cope with the stressful world that surrounds us?

Stress can make us sick.

It is never really the case that stress makes you sick, or even increases your risk of being sick. Stress increases your risk of getting diseases that make you sick, or if you have such a disease, stress increases the risk of your defenses being overwhelmed by the disease.

A large body of evidence suggests that stress-related disease emerges, predominantly, out of the fact that we so often activate a physiological system that has evolved for responding to acute physical emergencies, but we turn it on for months on end, worrying about mortgages, relationships, and promotions.

The book’s emphasis on the need to enhance the effectiveness of our coping mechanisms in the face of an increasingly stressful world is particularly relevant in today’s fast-paced and demanding society. The discussion of coping strategies and their potential impact on mitigating the detrimental effects of chronic stress is both enlightening and practical.

I particularly liked the way he wrote the story of how Roger Guillemin and Andrew V. Schally made great effort and chaos to discover the peptide hormone production of the brain and got the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1977, in such an amusing way.