There is nothing in the world, I believe, that would so effectively help one to survive even the worst conditions as the knowledge that there is a meaning in one’s life. What man actually needs is striving and struggling for a worthwhile goal, a dream, a freely chosen task.

When we, as humans, exist as mere stardust, biological component, chemical reactions, and under movements yet are driven by physical laws, seem don’t have the superpower to change the world or the situation around us. We are easy to fall into the black hole of emptiness, meaninglessness, and even further to Nihilism.

I like thinking out questions a lot. Although most of the time, I couldn’t think through the answers, the ones I did will eventually appear to be wrong or not sophisticated enough. And What’s the meaning of life? is one of them, and a giant one, that has been floating in my mind.

There are a handful of books that have permanently changed the way I view the world, the way I view life, and my constant state of mind. Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl is one of those rare books.

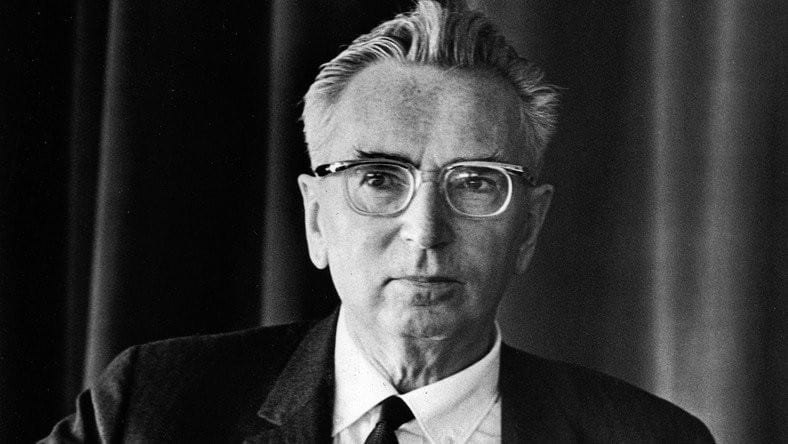

The author, Viktor Frankl was an Austrian, Jewish psychiatrist who pioneered logotherapy, a form of existential analysis focused on finding meaning in life. In 1944, Frankl was transported to the Auschwitz concentration camp (and other successive camps), where he endured a harrowing and unspeakable experience. In 1945, Frankl’s camp was liberated by American soldiers, and Frankl returned to his native Vienna, where he engaged in groundbreaking research on logotherapy and gained international fame for his teachings on finding meaning in life.

I stayed up late over two nights and switch over my regular podcast listening time, just so I could read this book. The lines and paragraphs were written in such a way that I have found myself, while and after reading, questioning things about my thought patterns and my responses to the ebbs and flows of day-to-day life.

Man’s Search for Meaning is a two-part account: the first half discusses Frankl’s experience at the concentration camps, and the second half is comprised of universally applicable lessons gleaned from Frank’s struggle.

Kept the survivors going, even in the most unthinkable conditions — at the concentration camp.

There are few such explicit, overwhelming, and absolutely honest accounts of life in the concentration camps. Frankl’s description of the emotional, spiritual, and social dynamics of his experience, as well as that of other prisoners, is tremendously humbling.

“The thought of suicide,” he recalls, “was entertained by nearly everyone, if only for a brief time. It was born of the hopelessness of the situation, the constant danger of death looming over us daily and hourly, and the closeness of the deaths suffered by many of the others.”

Frankl implicitly asks, throughout the book, what we have in our own life if we have nothing of the world. Who are we if we do not have our degrees, our family, our home, our name? If some or all of this is taken from us, what defines us? What keeps us going? And why?

One of the inspiring of all was a truly kindred soul that Frankl came across in the concentration camp: “We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Things determine each other, but man is ultimately self-determining.

Logotherapy, as described by Frankl, is neither teaching nor preaching. It is as far removed from logical reasoning as it is from moral exhortation. In his view, the more one forgets himself—by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love—the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself.

In the postscript of the book, Frankl defined tragic optimism: 1) turning suffering into a human achievement and accomplishment, in the face of pain; 2) deriving from guilt the opportunity to change oneself for the better, in the face of guilt; and 3) deriving from life’s transitoriness an incentive to take responsible action, in the face of death.

If one asks me to summarize in just one sentence, the Logotherapy, or even the whole book, I would say Nietzsche’s “He who has a Why to live for can bear almost any How.”

I recommend this book, this marvelous gift, to ones who are aiding in their soul-searching — have a question in their life, the question of meaning, at even, the meaning of their life.